Welcome to heartbreak hotel!

Stay for a while, have some coffee, talk about your problems.

We just want a little piece of your beating heart

heartbreak hotel is a text-based game you can download and play in your browser. It was made using Twine.

Anbu V

Welcome to heartbreak hotel!

Stay for a while, have some coffee, talk about your problems.

We just want a little piece of your beating heart

heartbreak hotel is a text-based game you can download and play in your browser. It was made using Twine.

The interaction between the art and access is relevant in the way visual representation was transformed in Edo period Japan with the rise of woodblock printing and the invention of affordable blue dye. Before the invention of Berlin or Prussian Blue dye in the eighteenth century[3], blue as a color evaded artists and their works. In fact, places where blue is seen as prevalent today, the sky and the sea for example, are frequently portrayed in other colours before the eighteenth century. There is evidence that these spaces weren’t even considered ‘blue’ in the way we presently think (Homer’s Odyssey famously describes the sea as “wine dark” and natural descriptions in Homer’s work entirely avoid blue for example).

Japanese artist Tawaraya Sotatsu’s depictions of water and waves are an important example of this pattern. Sotatsu’s Waves at Matsushima (Fig. 1) screens and the famous Anthology of the Thirty-Six Poets with Crane Design scroll (Fig. 2) both depict stylized waves and water and make interesting uses of color. John Carpenter cites Waves at Matsushima as an important piece of the Rinpa school of painting, emphasizing “the bold coloring”[4] and “experimentation with colored pigments”[5] that was prevalent during this time. Despite this experimentation with color, both Sotatsu’s work and the general body of art at the time depict water with colors like gold and white, as is done in Waves at Matsushima and the Anthology of the Thirty-Six Poets with Crane Design, rather than blue. Until the eighteenth century, blue denied artists access to itself and remained absent in most depictions of the natural world including experimental styles of illustration. Where blue was used, it was frequently in the process of fading and disappearing as blue pigments were commonly fugitive colours that faded when exposed to the environment.

However, following the lowering cost of Prussian Blue and its widespread availability especially in the nineteenth century, blue skyrocketed into use in Japanese art and particularly in Edo period print culture. This is visible in the work of artists such as Hiroshige and Hokusai. Hiroshige’s Cherry Blossoms at Night on Naka-no-chō in the Yoshiwara (Fig. 3)is a predominantly blue image that depicts the night sky in a familiar deep blue. Similarly, Hokusai’s immensely popular Great Wave (Fig. 4) pictorializes the ocean and Mt. Fuji in a bright, immediately recognizable shade of blue. Thus, spaces that were initially unable or unwilling to be represented with blue—the sky and sea—quickly became unanimously associated with it. It is also interesting that the widespread access to blue coincided with the explosion of print culture, a medium that inherently promoted the accessibility of art.

Unlike paintings, which were expensive and could not be shared, traded or distributed amongst larger groups of people, sharing, trading and ease of access were central to print culture. The rise of print culture in opposition to traditional painting also stimulated a kind of class rivalry between painting as an elite form that was much more inaccessible to the common public as compared to much more popular, affordable and accessible prints. The “blue revolution”[6] marked by the invention and widespread use of Prussian blue alongside the explosion of accessible print culture can be argued as indicative of the inherently human impulse to access and obtain particularly that which seems inaccessible or exotic. As Christine Guth writes, the use of blue in Edo period print culture became “a signifier of the exotic to represent familiar sites”[7].

Print culture also gave rise to a more complicated sense of collective authorship, as any one print could not be designated a single author. The process of woodblock printing, involving designers, woodblock carvers and colorists amongst others introduced a similar notion to what Christy Bartlett’s describes as “multiple hands producing a seamless whole”[8] when speaking about the collective authorship present in Kintsugi tea culture. Art history is particularly concerned with recognizing the inability of traditional notions of authorship to categorize works where a definite sense of authorship is complicated and perhaps even inaccessible.

I think what I find most important and interesting in art history is evaluating silenced or collective authorship along with the way concepts of inspiration, influence and copying are intertwined, raising questions on which voices last through history and which ones are silenced. The narrative of elite, individual authorship is an incomplete notion that ignores the role of influence, inspiration, collaboration and reinvention that is prevalent throughout history and predominantly ignores the universality of art in the human experience. As Yiengpruksawan argues about the Choju Giga ‘Animals scroll,’ the “vernacular culture of … commoner communit[ies]”[1] is just as relevant and important to art history as the “masterpiece of a great artist with an illustrious patron”[2].

It is not just powerful rulers and famous historical figures across history that are creating and have access to important art—it is all people across all times.

[1] Yiengpruksawan, Mimi Hall. 2000. Monkey magic: how the “Animals” scroll makes mischief with art historians. Orientations, V.31, N.3 (March 2000). Hong Kong: Pacific Magazines, 83

[2] Ibid.

[3] Christine Guth and University Of Hawaii Press, Hokusai’s Great Wave : Biography of a Global Icon (Honolulu: University Of Hawaii Press, 2015), 26

[4] Carpenter, John T, and Art New. Designing Nature : The Rinpa Aesthetic in Japanese Art. New York: Metropolitan Museum Of Art ; New Haven, 2012., 17

[5] Ibid., 18

[6] Christine Guth and University Of Hawaii Press, Hokusai’s Great Wave : Biography of a Global Icon (Honolulu: University Of Hawaii Press, 2015), 26

[7] Ibid., 29

[8] Christy Bartlett et al., FlickWerk : The Aesthetics of Mended Japanese Ceramics (Münster: Museum Für Lackkunst, 2008)., 12

Ravenous. I want more.

Silence. Not the kind that is full

ripe with possibility,

the potential of the unsaid,

but the silence that is empty.

the nothingness

the flicker of a failing lightbulb

the incessant breathing

falling seconds

empty time

no, not empty

full with regret

scared of something that doesn't exist

the now that is now gone

I miss you.

take heed of the sounds

the rocking feet

the cold night

it's the last time you feel them

I will miss you.

Goodnight wonderful self-aware stardust

you are a witness to this moment

alive and not numb

not yet

the stars sing to me

I wish I was home.

not perfect, but home.

Spaces and tabs are weird on mobile sometimes. Probably better on a computer screen

Possibility Across the vast ocean of possibility lie islands. Infinitely many in number and each infinitely far apart. Every passing minute land floats farther way. So many islands. Do any have that crucial One that you need? A mere glance at the stars. I wish to lie here forever. Gently rocked to sleep by the waves of the ocean of possibility. Oh sweet possibility! Forever and ever frozen in this instant. The sound of the stars and the wine-dark sea. The world stretched out before us. An infinite plane of infinitely many infinities. Bundled up in little dreams and held within tiny beating hearts. Your eyes light up. And there it is again. A rare wonderful world of in-betweens and un-invented. It’s possibility.

Untitled

In the vicinity of glowing embers

Neath’ the dome of a starry night

I hear them say

I hear

“sweet monstrous humanity

I am what you made.

In my veins flows your deepest sadness.

The secrets hidden so safely

they’ve been forgotten.

that dull familiar ache

the longing in the deepest crevices of your ribcage.

In my veins flows

what was brought by your words

that are my bones.

My skin is that leather which binds your stories.

And my heart?

the thumping pumping revealing mass writhing eternally

remember. a single error is all it takes.

My heart is all your lies.

The lies you speak that ring with the inevitable truth of your

reality.

These are your stories.

And I tell them to you,

firstborn human.

And you will tell them again

And when I die, you will birth me

And when humanity takes its last breath,

I will be there.

For you are immortal.

Immortal in these tales.

In the books

the letters

in the little cartoons

scribbled on the margins of a ruled sheet

years and years ago.

Monstrous.

You are as human as I.”

Or so I heard.

The Giant It seems so far away until it isn’t. Until it is at your heels Until they arrive. Where we were and where we will be collide and you can see neither despite feverish desire. And we float suspended in a bubble between thumb and forefinger of a Giant whose gaze pierces my lungs and uncovers the breath that never left. Nothing ever leaves. The thought refuses to leave The words refuse to leave my lips They rattle around in my skull The beast grows restless threatens to snap the bubble fingers rush together snuff out the flame-- that last living light-- leaving naught behind but the scent of a breath held but an instant too long.

It’s been three months since I posted anything.

Here’s some stuff I’ve been up to:

The coolest thing I’ve been doing (sorta) is getting back into making (or at least trying to make) games and interactive art after a long time. Train of Thought is my first complete game/interactive art. It takes 10 minutes to play through completely and is inspired by the experience of dreams, wakefulness and feeling time pass by. It’s not really a traditional game but I wanted to try and explore the stuff that’d go through the head of someone awake late into the night amongst some other stuff.

If you’d like to play it, click here. Once you’ve downloaded and extracted the zip file, you’ll find a text file titled “readme” which has a short note about the game, its controls and instructions on how to play. You’ll probably want to check that out before playing.

The game only works on Windows as of now (macOS is really annoying and just doesn’t work with this kind of stuff) so if you don’t have a Windows computer (nearly any windows computer will do) and still want to see what it looks like, you can check out a complete walkthrough of the game here.

Last month, I turned eighteen. That makes me a legal adult. Unsurprisingly though, I don’t feel any different—mostly because as anyone who’s experienced it would know, the transition between childhood and adulthood isn’t nearly as simple as our legal system might suggest. Of course, that isn’t really a fault in the way our legal system treats this phenomenon of age and adulthood. We do, after all, need some universally agreed marking point and that just so happens to be eighteen (which, in its defense, was probably decided after much thought and deliberation). But this classification has gotten me to think more and more about where I place myself in this spectrum. Because I think (in my infinite age and wisdom as an eighteen-year-old) that adulthood is less of a clear marker in your life that you steadily approach and more of waking up one day and realizing that things are just different. Or looking back and not being able to find the point when it all changed.

Because that’s just how things feel right now: different.

As of writing these words, I am hurtling through the air 40000 feet above sea level in a metal can that’s somehow statistically safer to travel in than a car driving down a busy street. I’m not surprised that many people—me included—find this fact odd. At once knowing that it must be true because there’s data supporting it and yet simultaneously being unable to truly accept it. I mean, no one plays a safety video when I’m getting on a car right?

I’m told I have approximately 10 hours and 40 minutes left before this journey concludes.

It’s fitting that I’m writing this from an airplane—a liminal space of travel if any. It’s a place that’s neither here nor there. Neither departure nor arrival. Suspended in the middle of the atmosphere. Or as indie game Glitchhikers describes, “the spaces between places” that “dominate our time but not our attention, where our minds are left to wander to parts of ourselves and our world normally left unexamined”—especially when you’ve got 15 hours all to yourself.

The reason I’m writing this is largely because right now, I find myself in this very space of in-betweens—attempting and failing to separate and unscramble the thorough mess of… “stuff”… that I find myself buried under.

But when I look out the window and see the infinite horizon stretched out, the pandemonium of colour and texture (for the sun has begun to rise), the anxieties take a backseat for a minute, and I feel the bizarre, small feeling again. And on the rare occasions that I find myself face to face with this feeling, the Earth feels just a little less suffocating and I realize why even this miraculous machine that I’m travelling on will still take another 10 hours and 6 minutes before it reaches the other end of the world.

The world isn’t that small.

There’s so many people. So many lives, each more intricate and nuanced than I could ever begin to fathom. And even this colossal world of ours and all of these lives are mere atoms in the vastness of existence.

But I’m rambling now.

We are sailors. Sailors braving the vast ocean of possibility—a term that embodies the collective human experience in many ways.

After all, so much of human experience lies in the in-betweens, in this weird unexplored no man’s land. So much of this relies on trudging, often unprepared and sailing without a compass across the oceans of possibility. At once stretches out infinitely many islands scattered across the unending turmoil of the ocean. And only one can be visited. The others float away, never to be seen again. Every minute land gets further and further away and I must decide on one of these islands before it’s too late.

But there’s just so many… and what if none of them have what I’m looking for?

Scratch that. Here’s a better question: what am I even looking for? What do I need?

I’ve got another 9 hours and 34 minutes left on this plane.

I need some sleep.

The title of this post is a reference to two really good comic books, Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow and the similarly titled Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader. They’re both super cool. So read them maybe.

I think what makes the camera so interesting as a concept is its relationship with the idea of objective reality and the contradictory nature of its attempt at being the single undeniable medium of objectivity. The camera promises to preserve reality as it is, capturing all that is within the frame as a single unmistakable truth. “This is how it happened,” it seems to say, presenting a reality that is far more reliable than the fleeting memory of a witness. But it’s here when placing the camera against the idea of memory that the very idea of objective reality begins to shift and come into question. Because, as much as it is considered an objective medium defined by the idea of being watched and recorded—like CCTV video surveillance promising a reality that is just as black and white as the footage it records—the camera can equally become a symbol of subjectivity.

Take the camera’s role in film. At its core, film reduces to one thing—perspective—how a series of events distilled into film is influenced, dramatized, altered or otherwise coloured by its presentation. Because film is undoubtedly influenced by the way it is presented—by the illusive quality of what’s in the frame and what’s not. And I’m not questioning whether the narrative presented in a film is real or not—it’s often not. Instead, I’m asking whether the camera presents a single objective narrative at all, regardless of real or fictional.

Buster’s Mal Heart is a surreal mystery film dealing with the experiences of a man struggling with a fractured psyche. It’s a film that deals with the constant threat of truth and fiction merging together into a reality that can never be trusted. And what I find particularly interesting about this idea is the way protagonist Jonah is forced to confront and reconcile his version of reality with the terrifying, ever-watchful eyes of a camera. Fractured by grief from the loss of his family, Jonah seemingly “invents” a series of events explaining the murder, beginning with his dealings with a mysterious man entering his hotel late at night and ending with the death of his family. And despite Jonah being entirely certain of this version of reality and the mysterious man’s role in his loss, the camera claims otherwise. The video surveillance system installed in the hotel reveals that not a single person entered the hotel but Jonah himself.

So… Jonah made everything up in his head and the camera saved the day with its objective, unbiased reality, right? Well… maybe? But maybe it’s not quite as simple.

“I don’t believe it”

Like the surreal imagery of Jonah splitting into two distinct versions of himself simultaneously taking two roads at once, maybe there’s more than just one truth. While the camera installed in the hotel seems to suggest that Jonah is merely a psychotic man responsible for his family’s death, I think the film equally suggests that he was a man controlled by isolation, sleep deprivation and mental struggle beyond his control. Maybe in the reality that we inhabit, there’s more than just one “real” version of events. And as much as the camera would like to, perhaps it doesn’t reveal everything that it says it does.

The Rashomon Effect, as explored by Japanese Filmmaker Akira Kurosawa (based on the work of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa) deals with the fragility of objective reality. More specifically, the Rashomon Effect deals with how multiple witnesses taken from the same scene notoriously have different accounts as to how the same series of events took place. Neither of the witnesses lie, but their accounts are all different, often influenced by differences in perception and personal biases. That doesn’t make any of the accounts necessarily more or less accurate though. Instead, it brings to light just how easily the narrative of a single ‘objective’ reality falls apart.

And returning to the idea of filmed images, what makes this even more interesting is when considering how our own version of events as an audience of a film or of an image is influenced by the way it is presented to us. Because perspective, sequence and timing play equally key roles in influencing the way we understand and percieve reality. Even something as simple as the angle that a camera is positioned introduces biases despite there being no change at all to the actual subject being filmed by the camera.

In the 1920s, Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov experimented with the responses of an audience towards short films that were edited differently. Kuleshov recorded how an audience’s reaction and the underlying meaning of the same exact video clip could be drastically altered simply by changing the clips that came before and after. The meaning behind a character’s reaction seemed to depend just as much on the clip that came before as the reaction itself. So, do Kuleshov’s film clips prove that the emotional responses of an audience are entirely unreliable, futile and contradictory? Not quite. Instead, I think it highlights the importance of context and perspective when viewing images filmed by a camera or even reality itself. A single video clip by itself doesn’t hold all the answers. And neither does a single camera or a single perspective, regardless of how “objective” that may be.

And while this phenomenon is usually used to describe the power of editing in film, I think it equally applies to unedited reality. Simply the way we view events and the order, context and timing with which we view or experience something can fundamentally change the way we percieve it.

But how then do we deal with the other aspect of the camera—that of still images and photographs? Graham Clarke believes that the photograph is “one of the most complex and problematic forms of representation” while Larry Ray points out that it is “essentially ambivalent” and “doubly defined by its relation to reality and the imagination. Thus, while more or less accurate and interpretive, and realism ‘has to be the first principle’, this cannot be without imagination, which is an essential dimension of the image.”

Still images don’t have clips that come before or after to colour their interpretation. But much like the memories of witnesses described by the Rashomon effect, they are influenced by the personal biases and interpretations that play a vital role in defining the moment of reality captured by the camera—a moment that is made even more mysterious when considering the photograph’s unwillingness to capture what came before or what happened after.

But this examination of the camera also begins to reveal the flawed nature of singular objective perspectives entirely. Because reality doesn’t always exist simply as we see it. There’s often much outside ‘the frame’ that we’re missing. And while the camera is contradictory when it comes to its objectivity, I think that’s more reflective of the lack of a single objective reality in the first place rather than any fault in the camera itself. The question of whether objective truth exists at all may be difficult to answer, but what I think isn’t difficult to conclude is the worth in atleast acknowledging and reconciling with the more abstract, intangible, subjective side of reality—as ‘unreal’ as that may initially feel.

As a child, I considered such unknowns sinister. Now, though, I understand they bear no ill will. The Universe is, and we are.

Solanum, Outer Wilds (2019)

In the time that I’ve been doing this thing, I’ve written a bunch of stuff that I’ll probably never finish or be completely happy with. But I figured instead of leaving them to just be on my computer forever I might as well put it all up here in one big pile. These are all a little incomplete, some more than others and I’ll probably add more stuff later. Some are missing either a bit in the middle connecting two ideas or a proper ending or they’re disjointed or something like that. So yeah, if you’d like to go through this big mess of small stuff that I’ve made, go ahead (also a lot of them have terrible titles, again because they’re incomplete).

On the Accident of Discovery

The existence of life beyond the confines of our isolated solar system is next to absolute. And this isn’t because of some universal rule or some unstoppable will. No, the Universe is entirely indifferent to our excitement. The reason behind this certainty is mere probability.

…..

Somewhere out there, maybe in our galaxy or beyond that, life must exist. And extending that idea, intelligent life likely does exist too. There’s even an entire paradox dedicated to dealing with the question of why we haven’t already encountered such life considering the likelihood of their existence (The Fermi Paradox). Statistically speaking, somewhere beyond our solar system there must exist individuals who think and feel just as we do—although, their means of interaction with the Universe could differ vastly from us. Either way, “they” probably exist. Somewhere.

Why do I bring this up?

Outer Wilds is a game where you are given exactly 22 minutes to hurtle into space in a tiny metal and wood canister that you call a spaceship and explore whatever you can. There are no objectives, no goals and no ominous markers pointing out the next mission or quest, unless you set one by yourself for your own reference.

And after those 22 minutes, the sun explodes.

The sun explodes into a brilliant, violent, all-encompassing supernova that you cannot escape no matter how hard you try (and I have tried). After that though, you are returned to the exact spot you were sitting exactly 22 minutes prior and are allowed to do everything that you did all over again. The only thing you retain is the knowledge you have gained in those 22 minutes, helpfully recorded by your ship log as you progress—as abstract an idea as ‘progress’ may be in a game like Outer Wilds. As many other players have pointed out, this is a game where the ‘upgrades’ and ‘abilities’ aren’t physical collectable things. Instead, they’re information. Your mind is the currency in Outer Wilds.

But that’s not truly the reason I’ve been sucked into this game. I attribute that to how uncannily familiar and ‘human’ it feels to play this game—which is ironic when considering that there isn’t a single human to talk to, read about or otherwise interact with in the game. There are ‘Hearthians’ and ‘Nomai’, fictional races of fictional beings in a fictional solar system, but no humans. Not a single one. But characters that do exist in this game are uncannily human.

For the last two weeks, I’ve been playing as one of those characters—one of only two Hearthians who are aware of this bizarre 22 minute time-loop. And as I explore the solar system around me in these 22 minute intervals, I confront odd things. I’ve found giant anglerfish and roasted marshmallows above a black hole. I’ve stumbled upon the final resting place of long dead explorers forever frozen in time holding on to each other in their final moments as they face a slow but inevitable death.

Sometimes I find things entirely on accident

…..

And I think this idea applies to humans exploring in the real world too. Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin (that later lead to the invention of antibiotics) by accidentally leaving a petri dish open until penicillin producing mold began to grow. Max Planck made a wild unbacked assumption that led to the discovery of Planck’s constant and gave birth to quantum physics. As humans in a universe that is utterly indifferent to our curiosity and exploration, we are often stumbling upon things entirely by accident. But I think there’s something more to these discoveries than just “being in the right place at the right time”.

Because not only are these accidents merely starting points from which we continue to explore, create, observe and record, it is our unrelenting ability to step out and explore even when faced with the vast overwhelming possibility of failure that enables these accidents in the first place.

It’s our willingness to venture out there and knowingly stumble (sometimes, literally) that leads us to find these amazing things. We as humans are defined by our inexplicable will to venture out and learn even when faced with the threat of stumbling and failing disastrously. We can’t always describe why we’re driven to do things. We’re emotional and unpredictable. But in the right situations, those our best traits.

An accidental series of physical and chemical reactions kickstarted a process that over billions of years led to you and me existing today. And we continue to perpetuate these accidental—but not entirely accidental—discoveries as explorers, thinkers and selfless collaborators.

We venture into the unknown, afraid but not unwilling.

We’re explorers. We dare to venture out where no one else has been. We dare to know just how much we don’t know and then confront those gaps. As a species, we’re not just surviving—we’re alive.

Batman and Colour

Colour is iconic—even for a character like Batman who is often defined by the very lack of colour. Over time, Batman has become unanimously associated with darkness—a figure that emerges from the blackness of the night, from the uncertainty of fear, and from the depths of the unknown. And in such a visual layout defined almost entirely by darkness, colour suddenly becomes a bold statement—one that carries deep implications for storytelling. And the impact of colour becomes more apparent than ever in the iconic animated film from the 90s, Batman: Mask of the Phantasm

Typically, in film and media, black and white, sepia, and other combinations of dull washed out colours, are universally representative of the past—perhaps owing to our inclination towards viewing the past as a time of simplicity. When depicting such a time of simplicity, it’s fitting to make use of an equally simple visual scheme. Colour, is reserved to convey the nuances of present day that require complexity and depth—or at least that’s how we percieve them.

It’s interesting then, that Mask of the Phantasm subverts this traditional dichotomy, choosing to convey the past as vibrant, colourful and in stark contrast to the undetailed darkness that overwhelms the present. The subversion of a traditional dynamic between now and then becomes especially interesting when considering the role of the past in defining the characters inhabiting this film.

For the idea of the past continuously dominates Bruce Wayne’s life, as brought out in the recurring symbolism present throughout the film. The large portrait of Thomas and Martha Wayne, the towering Wayne gravestone, even the Phantasm itself and the recurring graveyard cast an ever-present shadow of the past. The graveyard is, after all, a resting ground for those of the past, a site for people long gone. But as much as it is a site of legacy and the past, it is equally a site of transformation and boundary—another motif that plays an integral role in the film, especially in its themes of coming to terms with change and the past.

This is especially prevalent in the amusement park of the future which ironically, is transformed from a symbol of Bruce’s bright future into a dilapidated retreat for Joker’s insanity, mirroring what Batman often fears, he himself has become.

The present is dominated by darkness with a few carefully chosen moments of colour. The past is much the opposite, primarily characterized by vibrant bright colours, interspersed with short moments of darkness. The possibility of giving up the vow that eats away at his life—of relearning contentment—is refreshing and, as such, is marked by bright, vibrant colours. But as the villainy of Gotham’s corruption destroys this possibility, the familiar darkness of Batman returns to the colour palette, and with it comes Bruce’s transformation to Batman. The birth of Batman marks what is perhaps visually the darkest scene in the entire film with Bruce’s face being entirely obscured by darkness, and Alfred’s reaction serving as the only insight into how Batman may look. His subsequent fear magnifies the symbol of fear that Batman becomes. The birth of Batman and the loss of colour making way for the darkness of present day is also connotative of a loss of innocence, resigning Bruce to the seemingly thankless life as Batman.

And with Alfred’s reaction being the only point of reference, we are suddenly made aware of the extent of Bruce’s transformation.

As such, the only departure from the defining colour schemes of the past and present arise in carefully chosen moments such as Andrea’s return to Bruce’s life being marked by bright, vibrant colours and the previously mentioned birth of Batman being marked by close to complete darkness.

The reference to Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One, in Batman’s siege at a construction site, while being pursued by the law, becomes especially interesting when considering the thematic similarities between the two versions of Batman. Much like in Year One, Batman is driven less by vengeance, violence or anger and more by his empathy and his belief in those around him.

Mask of the Phantasm establishes a precarious balance between past and present, progress and reversion, making and unmaking, reflecting these dichotomies in the personal and moral struggles of the characters. For in this film, the real villain isn’t the Phantasm or the Joker. It’s the past, threatening to cut into the present and open up carefully suppressed regret. The film’s narrative structure leaping between flashback and present, uses colour as a means of communicating the state of its characters dealing with the past.

….

“you seem to be displaying an awful lot of empathy for a man who would’ve left you to die had he been in your place” – Alfred, Heart of Ice

“An eternal guardian. Without love. Without pity” – Mask of the Phantasm (Screenplay)

On Indie Games

There’s an idea that often comes up when discussing creativity, especially in mediums like videogames. It’s that of creative constraints—the idea that small independent artists and teams, having little to work with in terms of a budget or assets, are often forced to come up with creative, innovative and exciting ideas to overcome the limitations placed on them. And it’s an idea that I’ve become intimately familiar with thanks to my love for indie (independent) games. The indie side of videogames is a space where creativity and risks are openly welcomed and where the primary objective behind a game’s creation is often connection, expression and artistic growth rather than profit or revenue; a space where independent artists have no one to answer to but themselves and those who play their game. As such, they are free to experiment, take risks and defy traditional expectations.

And it’s in this realm of possibility where boundaries and constraints blur together, I found Hollow Knight/Grimm’s Hollow/Every other indie game I like

…

When asked to describe a game I love, it’s often not difficult to categorize that game and point out exactly what makes it so special to me. But every so often comes along a game that doesn’t lend itself nearly as well to categorization. Where the very idea of “genre” is brought into question or where describing the game by its genre does little to no justice in actually describing it.

These games often have an identity that far surpasses their genre. And because of this, it isn’t something easily described. It’s a culmination, a collage, of characters and stories connecting with each other to form something as complex and nuanced as a game’s world.

And maybe that’s why im so drawn to them.

….

Because as humans, our identities are not made of clear defining traits. As a person, I can’t just be distilled to a fixed set of arbitrary adjectives. We’re more nuanced than that. (Identity?)

….

Hollow Knight was initially released on Kickstarter and Kickstarter backers were allowed to create characters that would later become a part of this world. And these characters born from Kickstarter backers begin to breakdown the boundary between this fictional worlds and reality.

Because these characters, as fictional as they are, are a vessel for these real people. To transcribe their thoughts and ideas into these characters. I never have and probably never will meet any of these people. But in interacting with these characters, I have, atleast in a way, met a part of them.

…

And this subconcious, unnoticeable feeling is what’s truly defining of Hollow Knight. It’s a game where you don’t quite realize that you’re entering into a part of yourself and your thoughts until you’re already there. Where a dung flinging beetle can suddenly become a mirror reflecting the fear of being forced apart from friends and loved ones.

The Hollow Knight (character, not the game) is a vessel (that’s what they’re called in the game), supposedly empty of all emotion. But over the course of the game, it also becomes a vessel for our own feelings. Of our speculation and our curiosity and finally, of our empathy. Of our humanity. Which is ironic when considering that the vessels were created to be devoid of any of kind of human quality. But much like the Hollow Knight being tainted by ‘an idea instilled’, it’s difficult to shut out our emotions and our feelings. And having a place to realize those emotions and interactions in tangible, personalized connections is refreshing, maybe even necessary. And it’s something that only videogames can do. Atleast for me.

Saint-Malo, France. Photo by Clovis Wood Photography on Unsplash

Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See is not a work of horror. But I think there is something frightening lying within the depths of its immersive storytelling—uncertainty. By itself, uncertainty isn’t inherently frightening. Arguably, the very appeal of a book is the opportunity to get lost in its world and discover its characters—things that would remain mundane and uninspiring if not for the thrill of unfamiliarity and uncertainty. But when unfamiliarity turns to confusion and when that confusion is accompanied by an unforgiving tidal wave of utter and profound helplessness—that is when the uncertain becomes the terrifying. Using the Second World War as a backdrop, All the Light We Cannot See plunges its characters into the depths of helplessness and moral uncertainty and in the process, tests the extent of human empathy and questions the nature of personal morality.

Being central to the struggles of the book’s characters, uncertainty and ambiguity are brought out even in the structure of the book’s storytelling with its rapid and sporadic shifts in perspective serving as a prime example. Especially towards the beginning, the book’s chapters often last no more than two or three pages before a change in chapter is accompanied by a change in perspective. These shifts in perspective, initially limited between protagonists Marie-Laure and Werner, are predictable—comforting even. But as the uncertainty of the war sets in, the perspective changes shift away from these established and methodical conventions, straying to numerous other characters, both familiar and unfamiliar. And in the process, there arises a kind of sporadic uncertainty in the way we as readers percieve the book.

The narrative voice isn’t restricted to shifting between characters alone. Equally evocative of the uncertainty and confusion plaguing the book’s characters are the temporal shifts in narrative perspective. The book is divided into thirteen parts, each associated with a particular time period. As such, the book’s narrative frequently veers back and forth between these time periods with the sporadic temporal shifts helping convey the inability to define a rigid, unchanging moral structure in a rapidly changing moral climate. But what’s most interesting is that despite the frequent changes in time period and temporal perspective, the book is written entirely in the present tense—a format of writing that denies any form of clarity in the idea of ‘now’ when used alongside the malleable time period of storytelling.

Quoted in an article by The Guardian, writer David Mitchell speaks about the experience of using the present tense in his book, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet:

“Writing a historical novel in the present tense gave The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet a strange paradox. This already happened a long time ago, yet it’s happening now. Time is such an important character […] that I liked the idea of a narrative that surfed the crest of the present moment for six decades.”

And I think this idea applies closely to All the Light We Cannot See as well. By using the present tense in entirely different eras of time, the emerging “paradox” and contradiction in ‘then’ and ‘now’ becomes central to the novel’s exploration of a confusing, undefined moral landscape.

Throughout the book, there also remains a significant emphasis on numbers and counting, especially in the case of Marie-Laure, perhaps alluding to the safety and comfort of moral and personal stability.

“Her father estimates there are twelve thousand locks in the entire museum complex.” (28) “‘How many pages, Marie-Laure?’ ‘Fifty-two?’ ‘Seven hundred and five?’ ‘One hundred thirty-nine?’” (31) “Twenty heartbeats. Thirty-five minutes.” (418) “Six blocks, thirty-eight storm drains. She counts them all.” (76)

As Etienne remarks, “these numbers, they’re more than numbers” (360). They’re closure and stability in the face of growing moral confusion and uncertainty. But when this stability is uprooted—when it is replaced by confusion and instability, such as during the invasion of Paris in the book, this emphasis significantly diminishes, and numbers are used only reservedly.

“Marie-Laure has long since lost count of her strides” (77)

It’s only when Marie-Laure finds solace in her great-uncle’s home that the extensive use of numbers becomes prevalent once again.

“Marie-Laure wakes to church bells: two three four five.” (126)

There’s an undeniable comfort in the clarity and unambiguity associated with numbers—in walking “the paths of logic” (111) as the book puts it. But it’s the collapse of certainty and logic—the collapse of personal and moral stability and the rise of confusion and contradiction—that is central to the book’s exploration of personal and social morality.

Even the title of the book alludes to a contradiction: the light that cannot be seen.

“So really children, mathematically, all of light is invisible.” (53)

As such, sight and perception become equally relevant tools in contextualizing moral uncertainty—not only in the literal sense of how these characters perceive the world around them, but also in how their perception is influenced by an uncertain, ever-changing moral landscape. Marie-Laure’s blindness, of course, casts an ever-present shadow of uncertainty in perception. But equally, characters like Werner and Etienne’s perception of the world around them tints the novel’s exploration of confusion and moral uncertainty. For both Etienne and Werner are haunted. The apparitions they percieve—the red-haired girl, a casualty of war clawing at Werner’s sanity as a repeatedly appearing hallucination, Etienne’s struggles with shutting out the hallucinations of his mind, the hauntingly beautiful description of Madame Manec’s apparition following her death—become manifestations of their inability to come to terms with a world where it is impossible to know whether your actions, regardless of intentions, are right or wrong. The apparitions and lingering spirits of the past, though not real, serve as recurring reminders of a world where the consequences of an action are massive and devastating and yet, completely invisible until it’s too late.

“‘But we are the good guys. Aren’t we, Uncle?’ ‘I hope so. I hope we are.’” (360)

Werner’s role in the war is particularly insightful when considering how perception is warped by moral confusion. Werner joins the war not out of spite, hatred, or even duty, but simply because it is the only option offered to him that allows him to seemingly take control of his life and escape the mindless doom and destruction that inevitably awaits him at the coal mines. But in attempting to escape said destruction, he is plunged into a different kind of destruction—the collapse of morality. And so, in attempting to escape one kind of destruction, we often find ourselves thrown into the midst of another. Werner’s perception of choice exists merely as an illusion created by the moral instability that surrounds him.

And when perception is so heavily colored by the moral climate in which it resides, there arises an unsettling question: how certain are our beliefs and how consequential are our choices really? How do I know that what I believe is true and not merely the product of an inconsistent, or worse, an oppressive moral climate? And are my choices truly mine to make or are they merely the equivalent of asking a child whether they’d like to brush their teeth before or after a bedtime story? Serve the Reich with your body in the mines or serve the Reich with your mind, at war—a choice that isn’t actually a choice.

“Your problem, Werner, is that you still believe you own your life.” (223)

The apparent illusion of choice raises several uncomfortable questions. And while these questions may or may not have entirely rigid, definitive answers, I think there’s a start to be found when considering what is indeed certain in our lives. For what redeems Werner’s struggle with morality and what offers solace to Marie-Laure during times of instability are memories and instances of human empathy. All the Light We Cannot See seems to conclude that even when faced with the relentless confusion of moral ambiguity, there’s at least some solace to be found in the unwavering certainty of human empathy.

But the moral climate explored in the book raises another, equally uncomfortable, issue—one that concerns Werner’s deliberation with choice and raises the struggles of establishing empathy in a world that utterly devalues it in favor of apathy and indifference. For it’s this struggle between the indifference of the Reich and the fundamental human empathy of his childhood that plagues Werner throughout the book. There’s an exchange between Werner and Marie-Laure that I think captures this idea effectively:

“I have no choice. I wake up and live my life. Don’t you do the same?”, asks Marie-Laure, to which Werner replies, “Not in years. But today. Today maybe I did.” (469)

Werner’s story is undoubtedly one of tragedy—a boy thrown into the midst of a world that relishes in stripping him of his innocence and his human quality. And failing to conform to this indifferent world—where you are expected to relinquish all empathy just to survive—is often met with devastating consequence. But it’s only through defying the moral expectations laid out by the Reich and embracing his humanity and empathy that Werner is finally freed, for the first time since joining the war, to live and feel in control of his life. The aftermath of that defiance, however, as seen with Frederick, can be bitter and destructive. And this crushing helplessness—the overwhelming consequence of standing up against a brutally apathetic moral landscape—can be disheartening. The book doesn’t entirely answer this issue—I doubt anyone can offer an entirely complete answer. But it does offer some solace in the progress we’ve made and celebrates those who continue to stand up against indifference despite knowing the consequences.

As readers of a book, we are often merely observers guided by a voice to see the world through the eyes of the many characters inhabiting that book, remaining unable to interact with them. But there’s one passage in All the Light We Cannot See that defies this convention, one passage where Doerr seems to directly address us as readers, drawing us into the narrative:

“We all come into existence as a single cell, smaller than a speck of dust. Much smaller. […] Forty weeks later, six trillion cells get crushed in the vise of our mother’s birth canal and we howl. Then the world starts in on us”. (468)

The one thing that remains certain in an uncertain world, is the origin of our humanity and our desire for empathy. And even when it’s difficult to find moral clarity, doesn’t the fact that we’re even searching for it in the first place, mean something?

I like to think it does.

“Don’t you want to be alive before you die?”

All the Light We Cannot See, page 469

Soul (2021) by Pixar Animation Studios and Walt Disney Pictures

In an essay titled, The Sycamore Tree, writer John Green brings up an all too familiar question: “What’s even the point?”. It’s a question that often creeps into our minds—the slow, sinking realization that nothing we do in this world will remain and that we are ultimately doomed to be forgotten in an indifferent, uncaring universe. And in such a universe, it’s no surprise that we tend to keep asking why we’re even here in the first place. In Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the greatest supercomputer ever created attempts to answer “The Ultimate Question to Life, the Universe and Everything”, famously proclaiming the answer as “42”. Adams’ idea raises interesting questions, particularly regarding our tendency to search for some quantifiable version of meaning, purpose and objective in a world that is increasingly devoid of such a definition of purpose.

Pixar’s Soul marks another attempt at answering this terrifying question of purpose and it’s possibly the answer I connect with the most. Soul attempts to redeem what can often seem like a mindless, crushing existence dominated by aimlessness—contrasting the bright colors and vibrant personas of the Great Before against the mindless, bleak void of lost souls and hedge fund managers.

“Don’t worry, they’re fine. You can’t crush a soul here. That’s what life on Earth is for.”

The recurring subway becomes a reminder of this onslaught, “every day the same thing, day in and day out”. But in following Joe Gardner’s relentless search for purpose and his subsequent reconciliation with the lack thereof, Soul seems to suggest that life doesn’t necessarily need a grand, overarching purpose in order to carry value. The driving force behind a desire to live isn’t some “spark” or dominating objective but rather the connections and relationships we build with the everyday people around us. Joe’s confident dismissal of “regular ol’ living” ironically becomes the simplest line to encapsulate the film’s ideas.

“Those really aren’t purposes… That’s just regular ol’ living.”

But it’s regular old living that’s so wonderful.

Walking, staring at the sky, talking to people—it’s the often overlooked, seemingly ordinary things that make life worth living rather than a single-minded obsessive pursuit of purpose. And so, Soul’s answer to the age-old question isn’t “follow your dreams or your life has no value” or “grow up and learn to face harsh reality or you won’t survive” but rather simply to live and appreciate the experience of existing around other people.

Soul’s maple seed, John Green’s sycamore tree, Douglas Adams’ 42—these writers all suggest that life doesn’t need a dominating purpose. What it does need is simply to be experienced. In a universe that is devoid of purpose, we are freed from an arbitrary, predetermined ‘calling’. We make a difference, not by attaining some defined standard of ‘success’ but by bettering the lives of people around us. It’s the simple interactions between people—a teacher like Joe inspiring a kid, a barber like Dez getting to meet amazing people and making them happy, or just someone gazing at a maple seed in wonder—that make life what it is.

“I may not have invented blood transfusions, but I am most definitely saving lives.”

In being consumed by a singular vision, it’s easy to get lost in a romanticized version of that vision and lose sight of what we’re truly after. After Joe’s performance of a lifetime, he’s forced to ask, “so what happens next?”, to which Dorothea replies, “we come back tomorrow night and do it all again”. It’s a cycle, much like what Joe has been running away from his entire life. I think what he wanted wasn’t simply to perform Jazz with Dorothea Williams but rather to escape the oppressing cycle of the subway and the all-consuming fear of purposelessness.

And the answer to that purposelessness lies in acknowledging the undeniable impact that everyday people have on each other. We as humanity consistently overcome hardship because we are driven to hold onto one another even in times of physical or moral crisis. And so, it’s not the exhilarating performance in front of a cheering audience that makes Joe give his second shot at life to Soul 22, but rather spending a day watching her live.

The greatest enemy of life isn’t purposelessness. It’s shutting ourselves off from experiencing life, in the name of ‘success’.

We don’t change the world by fulfilling some arbitrary definition of success. We change the world through the people we share our lives with and the things we care about, no matter how simple or small they are. Albert Einstein, Amelia Earhart and George Orwell couldn’t help Soul number 22 see the point of living—but Joe Gardner, the average man living an average life, could.

You realize you are in the vast dark shade of this giant tree… and that’s the point.

John Green, The Sycamore Tree

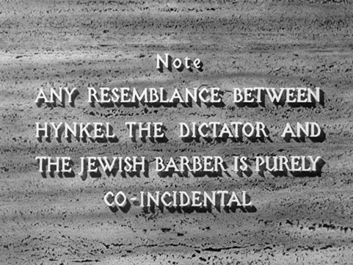

In 1939, legendary comedian Charlie Chaplin, financed by his own self-owned studio, wrote, directed and produced a film that openly laughed in the face of Hitler and his bigotry. ‘The Great Dictator’ loudly condemned Nazi Germany and set a standard for social criticism with its grounded exploration of human struggles—all while the United States continued to stay neutral in terms of its dealings with Nazi Germany.

Comedy, satire, mockery—always manages to worm its way into places where it is unwanted, exposing the fallacies of the corrupt and openly flaunting that which was meant to be hidden. While, on the surface, a light-hearted genre, comedy is also the perfect genre to pose and answer the more uncomfortable questions of much more serious issues. The idea of invading prohibited territories, exposing the silent and throwing light on shadow is one that forms the core of satire, constituting its defining traits as loud, outspoken, blatant, and unafraid of consequence—the perfect counterpart to the fear and silence that enables tyranny.

Kennan Ferguson describes comedy as “a subverting of the normative stitching of politics”, further describing “the power of the medieval jester, the coyote trickster, the Greek cynic, the literary satirist, and […] the late-night television comedian, all of whom possess a tremendous power: the ability to say the unsayable, to confront hypocrisy, to kick the pricks.”

Satire of the corrupt defines itself with this intolerance of the intolerant, making a mockery of bigotry and tyranny. As a genre, comedy bases itself on transgressing boundaries and remaining uncensored, loudly making itself heard by as many people as possible. And in the modern cultural landscape, arguably defined by the expressiveness of artists and media, comedy and satire are just as, if not more relevant than they’ve ever been.

Take Taika Watiti’s Jojo Rabbit—a film that uses comedy to “pierce and deflate the hideous bubble of Nazi ideology” and as such often makes clear the importance of remembering and acknowledging history. But in speaking about the idea of remembrance, writer David Reiff argues, with examples, that memory can itself be abused to support hate or violence in the modern world.

But regardless of how true those ideas are, what makes comedy’s version of remembrance so special—what often sets it apart from the all the other serious and straight-faced genres of art and media—is that it manages to break down barriers in discussion and facilitate open discourse on these social issues through a lens of vulnerability and growth rather than hate or spite. Comedy promotes the accessibility of discourse and discussion. Jojo Rabbit being an “anti-hate satire” as its tagline suggests, succeeds in acknowledging the past with sincerity while also facilitating discourse that celebrates the everyday people that stood up against hate during times of moral crisis.

And speaking about the celebration of the everyperson, I am reminded of the words of humorist Finley Peter Dunne’s Mr.Dooley, who remarked that newspapers should “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable”. And building on these words, writer and satirist Will Self concludes:

“If […] the work (satire) is mis-targeted—so afflicting the already afflicted, or comforting those already well-upholstered, (it is) […] merely offensive, or egregiously offensive.”

Comedy often celebrates the underdogs and the everyperson.

And so, comedies like Jojo Rabbit and The Great Dictator offer not a tasteless belittling of tragedy or a spiteful reminder of cruelty but rather a mockery of those who enabled hate and a much more genuine celebration of the everyday people that stood up against it—comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable, as Finley Peter Dunne would put it.

And this celebration of the personal, of the everyperson, becomes equally relevant in today’s cultural landscape with the rise of modern humour and its often surreal or absurd characteristics. Because, as a genre, comedy has always been predicated on the idea of rebellion—of challenging and even uprooting established conventions and institutions. Comedy revels in the unexpected, in the shocking, the sudden—in the very violation of reason and logic. So, it’s fitting that modern humor rebels even against it’s own against the established structures, challenging the very expectation of what makes a joke funny in the first place. And comedy’s obsession with rebellion makes it ever more the champion of the everyman, becoming a means for us to manifest and rebel against the uncontrollable absurdity and irreconcilable emotions that we encounter everyday, alongside the frenetic spread of information that defines the modern age. It is free to break from the established structure of a joke and explore the bizarre, absurd world we often find ourselves in.

In speaking about the relevance of humor in today’s cultural landscape, Rachel Aroesti writes: “Between the TV landscape and disaster politics, this return to ridiculousness feels refreshing and necessary” and similarly describes the ‘sadcom’: “a strain of comedy-drama shuddering under the weight of personal hardship and the idea that actual jokes are largely unnecessary. Things are funny because they are wilfully jarring and strange.”

And so, this strained relationship with logic, this collapse of reason and rebellion against predetermined notions becomes a celebration of the personal and the everyperson. Like, the ever-popular, intangible but irresistible relatability of ‘Wednesday Frog’.

For comedy as an art form celebrates everyday people. And, it makes a mockery out of those who perpetrate hate and tyranny. Tyrannical regimes fundamentally rely on blind faith and their illogicality silently going unnoticed. It’s fitting then, that they are shunned and mocked by the very genre that revels in exaggeration, repetition and the open flaunting of illogicality. Only, in the case of these regimes, exaggeration is often unnecessary, as their ideas, even at their core, are purely nonsensical, thriving entirely on fear and the cowardice of people in power.

Even today’s humor as, once again Rachel Aroesti puts it, “is characterised by a straightforward silliness, machine-tooled to pierce the panic-inducing online news cycle.” It’s a medium that embodies our potential for change, resistance and revolution—both in the way we talk about social and cultural issues and in the issues themselves.