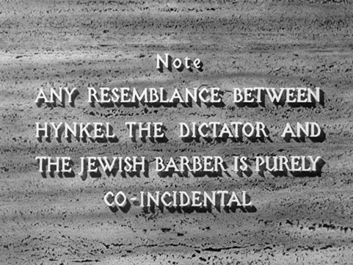

In 1939, legendary comedian Charlie Chaplin, financed by his own self-owned studio, wrote, directed and produced a film that openly laughed in the face of Hitler and his bigotry. ‘The Great Dictator’ loudly condemned Nazi Germany and set a standard for social criticism with its grounded exploration of human struggles—all while the United States continued to stay neutral in terms of its dealings with Nazi Germany.

Comedy, satire, mockery—always manages to worm its way into places where it is unwanted, exposing the fallacies of the corrupt and openly flaunting that which was meant to be hidden. While, on the surface, a light-hearted genre, comedy is also the perfect genre to pose and answer the more uncomfortable questions of much more serious issues. The idea of invading prohibited territories, exposing the silent and throwing light on shadow is one that forms the core of satire, constituting its defining traits as loud, outspoken, blatant, and unafraid of consequence—the perfect counterpart to the fear and silence that enables tyranny.

Kennan Ferguson describes comedy as “a subverting of the normative stitching of politics”, further describing “the power of the medieval jester, the coyote trickster, the Greek cynic, the literary satirist, and […] the late-night television comedian, all of whom possess a tremendous power: the ability to say the unsayable, to confront hypocrisy, to kick the pricks.”

Satire of the corrupt defines itself with this intolerance of the intolerant, making a mockery of bigotry and tyranny. As a genre, comedy bases itself on transgressing boundaries and remaining uncensored, loudly making itself heard by as many people as possible. And in the modern cultural landscape, arguably defined by the expressiveness of artists and media, comedy and satire are just as, if not more relevant than they’ve ever been.

Take Taika Watiti’s Jojo Rabbit—a film that uses comedy to “pierce and deflate the hideous bubble of Nazi ideology” and as such often makes clear the importance of remembering and acknowledging history. But in speaking about the idea of remembrance, writer David Reiff argues, with examples, that memory can itself be abused to support hate or violence in the modern world.

But regardless of how true those ideas are, what makes comedy’s version of remembrance so special—what often sets it apart from the all the other serious and straight-faced genres of art and media—is that it manages to break down barriers in discussion and facilitate open discourse on these social issues through a lens of vulnerability and growth rather than hate or spite. Comedy promotes the accessibility of discourse and discussion. Jojo Rabbit being an “anti-hate satire” as its tagline suggests, succeeds in acknowledging the past with sincerity while also facilitating discourse that celebrates the everyday people that stood up against hate during times of moral crisis.

And speaking about the celebration of the everyperson, I am reminded of the words of humorist Finley Peter Dunne’s Mr.Dooley, who remarked that newspapers should “comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable”. And building on these words, writer and satirist Will Self concludes:

“If […] the work (satire) is mis-targeted—so afflicting the already afflicted, or comforting those already well-upholstered, (it is) […] merely offensive, or egregiously offensive.”

Comedy often celebrates the underdogs and the everyperson.

And so, comedies like Jojo Rabbit and The Great Dictator offer not a tasteless belittling of tragedy or a spiteful reminder of cruelty but rather a mockery of those who enabled hate and a much more genuine celebration of the everyday people that stood up against it—comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable, as Finley Peter Dunne would put it.

And this celebration of the personal, of the everyperson, becomes equally relevant in today’s cultural landscape with the rise of modern humour and its often surreal or absurd characteristics. Because, as a genre, comedy has always been predicated on the idea of rebellion—of challenging and even uprooting established conventions and institutions. Comedy revels in the unexpected, in the shocking, the sudden—in the very violation of reason and logic. So, it’s fitting that modern humor rebels even against it’s own against the established structures, challenging the very expectation of what makes a joke funny in the first place. And comedy’s obsession with rebellion makes it ever more the champion of the everyman, becoming a means for us to manifest and rebel against the uncontrollable absurdity and irreconcilable emotions that we encounter everyday, alongside the frenetic spread of information that defines the modern age. It is free to break from the established structure of a joke and explore the bizarre, absurd world we often find ourselves in.

In speaking about the relevance of humor in today’s cultural landscape, Rachel Aroesti writes: “Between the TV landscape and disaster politics, this return to ridiculousness feels refreshing and necessary” and similarly describes the ‘sadcom’: “a strain of comedy-drama shuddering under the weight of personal hardship and the idea that actual jokes are largely unnecessary. Things are funny because they are wilfully jarring and strange.”

And so, this strained relationship with logic, this collapse of reason and rebellion against predetermined notions becomes a celebration of the personal and the everyperson. Like, the ever-popular, intangible but irresistible relatability of ‘Wednesday Frog’.

For comedy as an art form celebrates everyday people. And, it makes a mockery out of those who perpetrate hate and tyranny. Tyrannical regimes fundamentally rely on blind faith and their illogicality silently going unnoticed. It’s fitting then, that they are shunned and mocked by the very genre that revels in exaggeration, repetition and the open flaunting of illogicality. Only, in the case of these regimes, exaggeration is often unnecessary, as their ideas, even at their core, are purely nonsensical, thriving entirely on fear and the cowardice of people in power.

Even today’s humor as, once again Rachel Aroesti puts it, “is characterised by a straightforward silliness, machine-tooled to pierce the panic-inducing online news cycle.” It’s a medium that embodies our potential for change, resistance and revolution—both in the way we talk about social and cultural issues and in the issues themselves.

Perhaps one of your most detailed and researched pieces yet. Loved the argument and thoughts you presented shaaah anbaaa

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks

LikeLike

very unproffessional comment, dissapointed…

LikeLike